Q: Hello Jeannot, thanks for joining us. Can you tell us a little about yourself? Your background, your interests, your dreams?

My experience of attending public Montessori school in Texas developed so many of the qualities that I now consider key parts of my personality. I can trace my resilience, independence, urge for life-long learning, and even my own self-discipline back to the structure of formative years in Montessori. It’s no wonder that I aspired to become a teacher myself, to give back to the profession that had given so much to me. Was I in for a rude awakening! After working to obtain a bachelor’s of education and teacher’s certificate on scholarship at University of Dallas in 2008, I felt like landing a kindergarten teaching job in public school was a dream come true. Oh, but how crestfallen I was to find my classroom contained scarcely more than tables and chairs, a shelf, and binders full of worksheets. Conventional schools are nothing like my memories of Montessori. Frankly, I found the materials grossly inadequate and the approaches scattered and constantly being either micromanaged or overhauled. Try as I might to adapt traditional methods to what I know works from the Montessori style of education, it was too much of an uphill battle.

I am so glad I stuck with education. My hopes to give back, of the same quality that I had been given, came true in 2012 when I was able to interview to work at a new school innovation. Based on parent petition, the district would be transforming Dallas neighbourhood school Eduardo Mata Elementary into a public, open-enrolment Montessori school. Attending Montessori training toward the international teaching diploma (AMI) was a spiritual experience. I would leave the long days of training in specialized materials and philosophical implications feeling like we were doing something much bigger than just teaching math, teaching reading. The underpinnings of every aspect of Montessori pedagogy leads you to the discovery of the dignity of the child, the dignity of the human person, and the capacity for a peaceful child to bring about a better kind of world for all of us.

To any teacher considering Montessori, I have to tell you, bringing Montessori to a Title I, poverty-population with no competitive enrolment, in the public sector, is a daily inspiration. Our public school administrators have been patient with us, giving us time to demonstrate what we can do. We were nervous, wondering if we could pull in those national scores that earn autonomy from demands for drill-and- kill so common in some districts. We wondered what our appraisals would be like in a system of pay-for- performance for teachers. And we have worked our tails off—in addition to all of our Montessori training, my peers and I who did not yet have masters degrees in education enrolled ourselves to study early literacy, Montessori, and dyslexia at schools like Southern Methodist and Dallas Baptist here in Dallas. Good isn’t enough; if we were to prove to those looking down that the public need Montessori, we would have to put in our best.

If Montessori is a spiritual experience, this is where we had to extend our faith. To our great and continued celebration, our work has been recognized as a dynamic way of differentiating instruction for diverse learners, supporting student-centered instruction, and getting each child interested in working on just the skill they need to move to the next level. Best of all, visitors saw the fire of curiosity burning in our students.

For myself, I am looking forward to beginning a doctorate of education in urban leadership at Johns Hopkins University, by distance, next school year. I know the future is broad with possibilities, but the idea of opening up more access to the quality of education I’ve seen in public and private Montessori keeps me energized in the classroom—or as we call it, the House of Children—every day.

|

| Jeannot with his instructional coach Vicki Sampeck |

Q: What was your first experience with Montessori?

My family didn’t have money for anything like private school, like Montessori. The context of early-90s inner city of Dallas, Texas, before it was gentrified with organic food shops and chic pizza taverns and vintage shops, it was almost ruins. The public schools at the time had poor reputations due to overcrowding, violence, drugs, gangs, graffiti, and teen pregnancy. The high school near me was Sunset, something people used to mock in those days for representing the end of hope for the kids. That’s the worst, isn’t it? Dallas has seen such a transformation since then, and campuses like Sunset are now models for turn-around. My parents told me it gave them anxiety to wonder what their options could possibly be for getting their two kids a good education.

One day, at a thrift store—a charity store, in the US– a mother started up a conversation with my parents about a school she found for her children. A public Montessori school deep in the south side of town, an area notorious for poverty and civic depression. But she said it was exceptional and worth applying and sending the kids braving a bus ride from anywhere in the city.

I was eight when I first visited Harry Stone Montessori, one of Dallas’ three public Montessori schools now, and I still recall marvelling over children speaking in quiet, friendly tones in the cafeteria, on red-checkered table cloths with fresh flowers in the middle of the tables. The children seemed to be some other kind of being, the way they moved so independently through their mixed-age classrooms, working on their own in the halls and without anyone directing from the front of the room at all. My younger sister Jackie and I flourished there, all the way up to 8th grade.

When I was nine years old, just beginning my upper elementary years at Stone, I decided I wanted to be a Montessori guide just like my teacher, Mr. Hoffman. His gentleness, peace, and sense of humor lent themselves well toward being idolized as my childhood role-model. (I was a bit shy around him, however, and told him I wanted to be a palaeontologist when he asked, ha!) It would be almost twenty years before life would make that a possibility for me, but I never let go of the vision of the grace, peace, and independence I saw at work there as a child. I wanted everyone to be able to have what I saw there. I love that he is still a mentor for me, as a male Montessorian and now multi-generational Montessorian myself. My youngest, five, is a Montessori child now!

|

| Jeannot with his five year old |

That day, I had been sitting on the floor with a group of children, looking through cards for the enrichment of vocabulary. You will have to bear with me on this background information to get to the fascinating part of this story– Because Texas is a bilingual state, most of our early childhood materials come with Spanish on one side and English on another, color-coded. My students are in an English class, so they know to use the English side for reading.

I had one stubborn child, whom we can call Elijah. (Stubborn children are my favorite, if we get to pick a favorite quality, because I am stubborn, too!) This stubborn child continued to flip to the “wrong” side and leave his work incomplete, despite my instructions. In our method of logical consequence, if a child is misusing materials, you can help them put it away and chose a different activity until they honor instructions.

But that night— and here is the magic. My dream resumed this moment of reaching to pick up Elijah’s materials. In walked an appraiser, as constantly happens in public schools. The small woman sat down at the rug near me, quite silently for a long time, observing. Finally, I explained that we had been working on a vocabulary presentation. She nodded, “What is he doing,” gesturing to the boy. I answered, but she simply asked again, directing my gaze away from her and back to him.

It was an epiphany: Elijah was reading to himself in Spanish. He didn’t speak Spanish, but his peers did, and he was taking it upon himself become his own teacher. “He cannot obey you more than his inward urge to learn,” she smiled, and again pointed to Elijah. “What is he doing?”—this time, asking in a way to remind me to keep watching the children. And I saw her, in the dream, crocheting a beautiful doily. At that moment, I realized that perhaps I had been so lucky as to be visited in my dream by the Dottoressa herself, or at least to be visited by my heart’s understanding of her powerful message.

Our work is to watch and learn from the child, so that we may serve her and give her everything she needs to build her own success. Never teaching, never covering or checking off lessons; always guiding, always gifting the heritage of human understanding. I think often of the kind face in my dream that reminded me, at a moment I needed to hear it.

|

| A child at Jeannot’s school making bean burrito, which requires the integration of many practical life skills. |

Q: What’s your favourite Montessori quote? And why?

“All our handling of the child will bear fruit, not only at the moment, but in the adult they are destined to become.”

There is so much in our environments placed there with intention and honor for the child. I think, sometimes we can wonder how important it really is to follow exacting details of our practice, according to this rigorous training. In this pedagogy, we think often about the child who is coming to be and all we cannot see or measure at this time. When we strive to put real paintings on the walls of our class, when we search for real glass vases for fresh flowers in the rooms, when we use real wood in our materials, and when we begin presenting cursive to the three-year-old child, we send her a message: “You, child, are so valuable that we want to offer you the finest that we have as a culture, made from human hands. We trust in your ability.” We have such a special opportunity to invite the child to take part in a long, collaborative story of learning.

I love the intangibles. You can buy a whole classroom set of materials and set them on the shelf, but it is the sense of community that comes from the multi-age classroom and developing independence in the space that truly makes it come alive. There is a kind of compassion and empathy—social cohesion—that comes out of our Montessori spaces that has a power to grow and develop as the child grows and becomes an adult. Yes, our presentations serve the needs of the present child, but they also have the capacity to be the seeds that grow within a community for a whole and developed culture. It’s never just one child.

|

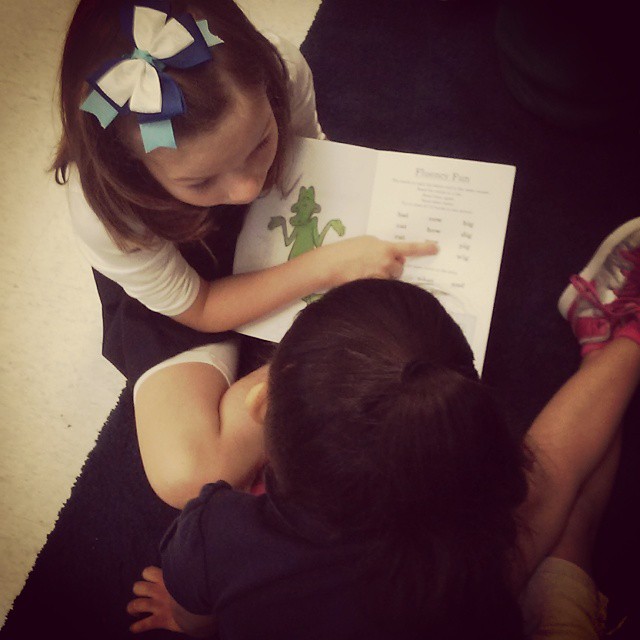

| Pictured above is an older child scaffolding the learning of a younger one |

Q: Is there a Montessori material you love particularly and why?

What would it mean, around the world, if all children began the study of culture at the age of three with The Sandpaper Globe, a globe with no political divisions? This is all of our home. Then, in early geography study with the Puzzle Maps, as children advance to study continents and all the countries within continents, they gain such an early sense of human unity. I adore the culture folders, giving very young children photos of our diverse ways of meeting fundamental needs in different places. It sounds so simple, but under rising tides of racism and nationalism, these simple messages offered to the foundational, Absorbent Mind of the child have the capacity to shape future society’s vision of our unity across borders and color.

What would it mean, around the world, if all children began the study of culture at the age of three with The Sandpaper Globe, a globe with no political divisions? This is all of our home. Then, in early geography study with the Puzzle Maps, as children advance to study continents and all the countries within continents, they gain such an early sense of human unity. I adore the culture folders, giving very young children photos of our diverse ways of meeting fundamental needs in different places. It sounds so simple, but under rising tides of racism and nationalism, these simple messages offered to the foundational, Absorbent Mind of the child have the capacity to shape future society’s vision of our unity across borders and color. When I think about Dr. Montessori and the geography materials, I think about her context of living through two world wars, having been exiled from her beloved Italy for challenging fascism, and becoming a friend of Gandhi while in India. The concerns which inspired these materials, and the promise of peace still offered by the child who can grow and transform society, remain with us today.

In the South, and really in large areas of the United States, teachers still struggle greatly with how to begin lessons and presentations that build a notion of tolerance for diversity, at a developmentally appropriate level. Without knowing exactly how to go about it, we know that respect for plurality—and all the value we must impart for Black lives and lives of color, women’s lives, elder lives, trans lives, disabled lives, immigrant lives, impoverished lives, queer lives, along with many other marginalizing and privileging identities– is an essential component of democracy. In the Montessori geography presentations, we find a way to begin those conversations of unity with a small child, in a way accessible to their senses. It’s really quite moving.

|

| Jeannot (to the left) with children playing the Parachute game |